It’s been awhile since I’ve had proper Edomae-style sushi, and I found myself returning to an intimate eight seat counter at Sushi Shikon, a renowned three-Michelin-starred restaurant helmed by Chef Yoshiharu Kakinuma. It was a really interesting night, as six of the eight patrons that night were familiar guests and knew the chef so things got a bit rowdy as the alcohol flowed and the night progressed.

The restaurant is an offshoot of the prestigious (also) three-Michelin-starred Sushi Yoshitake in Tokyo’s Ginza district, and has maintained its three-star Michelin status from 2014 until now. Sushi Shikon originally opened in 2012 under the name Sushi Yoshitake, but rebranded to Sushi Shikon in 2013 to avoid booking confusion with its Tokyo counterpart. It relocated from its original location in Sheung Wan to its current location in Central in 2019, into an understated minimalist space containing traditional Japanese decor - pottery, paintings, and traditional craftsmanship.

Chef Yoshiharu Kakinuma, often affectionately called "Chef Kaki," originally wanted to play rugby professionally when he was young, but his love of the culinary arts brought him ask to apprentice under his father. His father flatly rejected him and told him to apprentice outside the family, and this led Chef Kaki to three-starred Chef Masahiro Yoshitake, whom he joined as a kitchen helper. He rose up the ranks apprenticing at Sushi Yoshitake for several years, before moving to the United States and operating sushi restaurants in New York and Atlanta. He got back in touch with his mentor when Chef Yoshitake asked him to open his first restaurant in Hong Kong.

Chef Kaki is a staple behind the sushi counter every night and engages warmly with guests, explaining the intricacies of his craft and sushi etiquette during the omakase experience. Chef Kaki’s expertise lies in his mastery of aging and marinating the fish to enhance its flavors. His signature dishes, such as sake-steamed Shimane abalone with a velvety liver sauce, showcase his ability to balance tradition with creativity.

Sourcing the freshest seasonal ingredients daily from Tokyo’s Toyosu market, Chef Kaki ensures each piece of sushi and accompanying dish reflects the pinnacle of Japanese culinary artistry. His charismatic presence and dedication have made Sushi Shikon a standout destination for sushi aficionados in Hong Kong and one of my two favourite omakase counters that I keep returning to.

A expertly crafted hinoki leaf inset into the sushi counter.

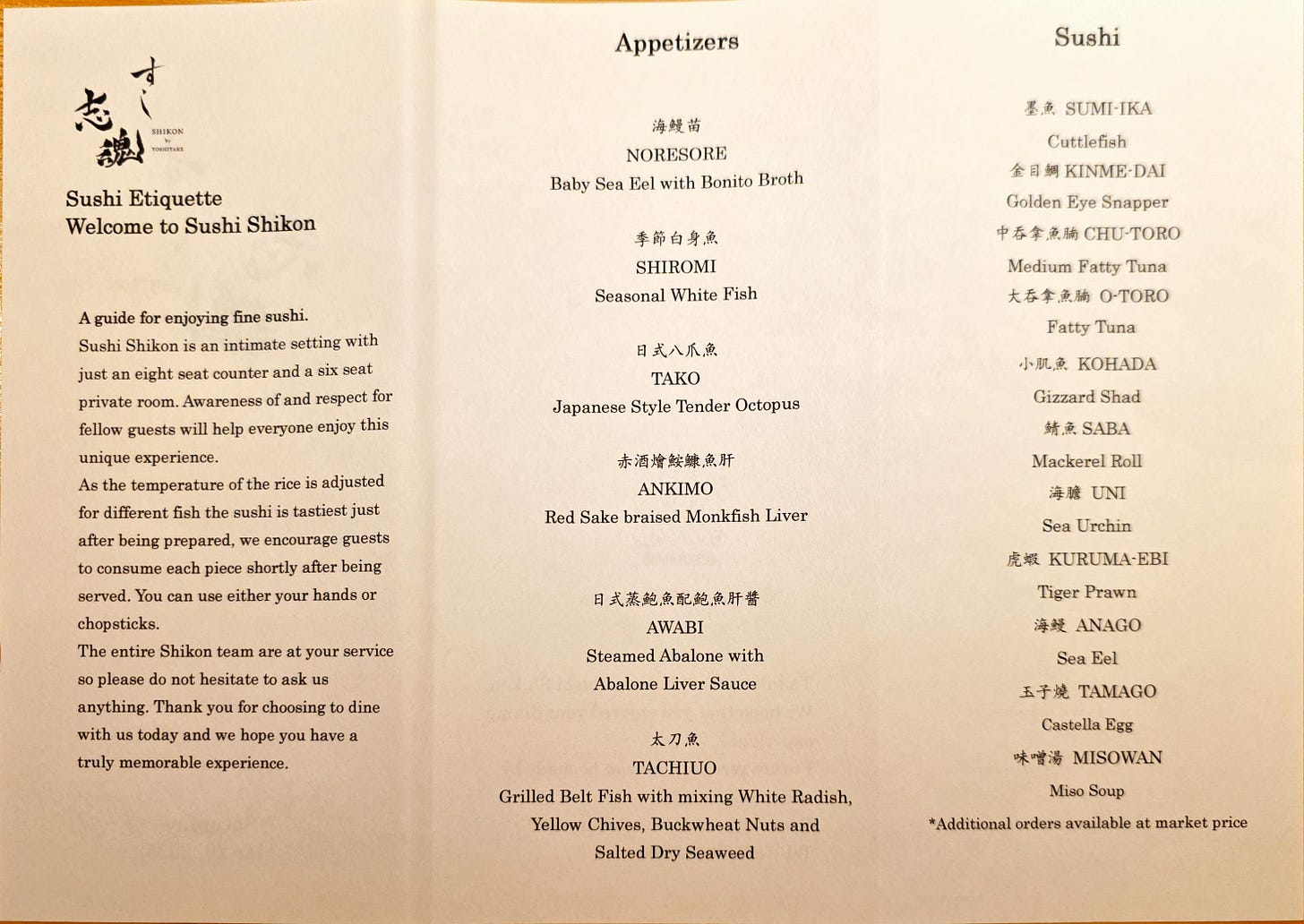

Stepping into the eight seat sushi counter, I was met by Chef Kaki, his young, attentive apprentice, and a smartly-dressed server. I was presented with the menu for the night, and given a glass of cloudy sparkling sake.

A Shichiken Yama-no-Kasumi Cloudy Sparkling Sake, from the Yamanashi Prefecture.

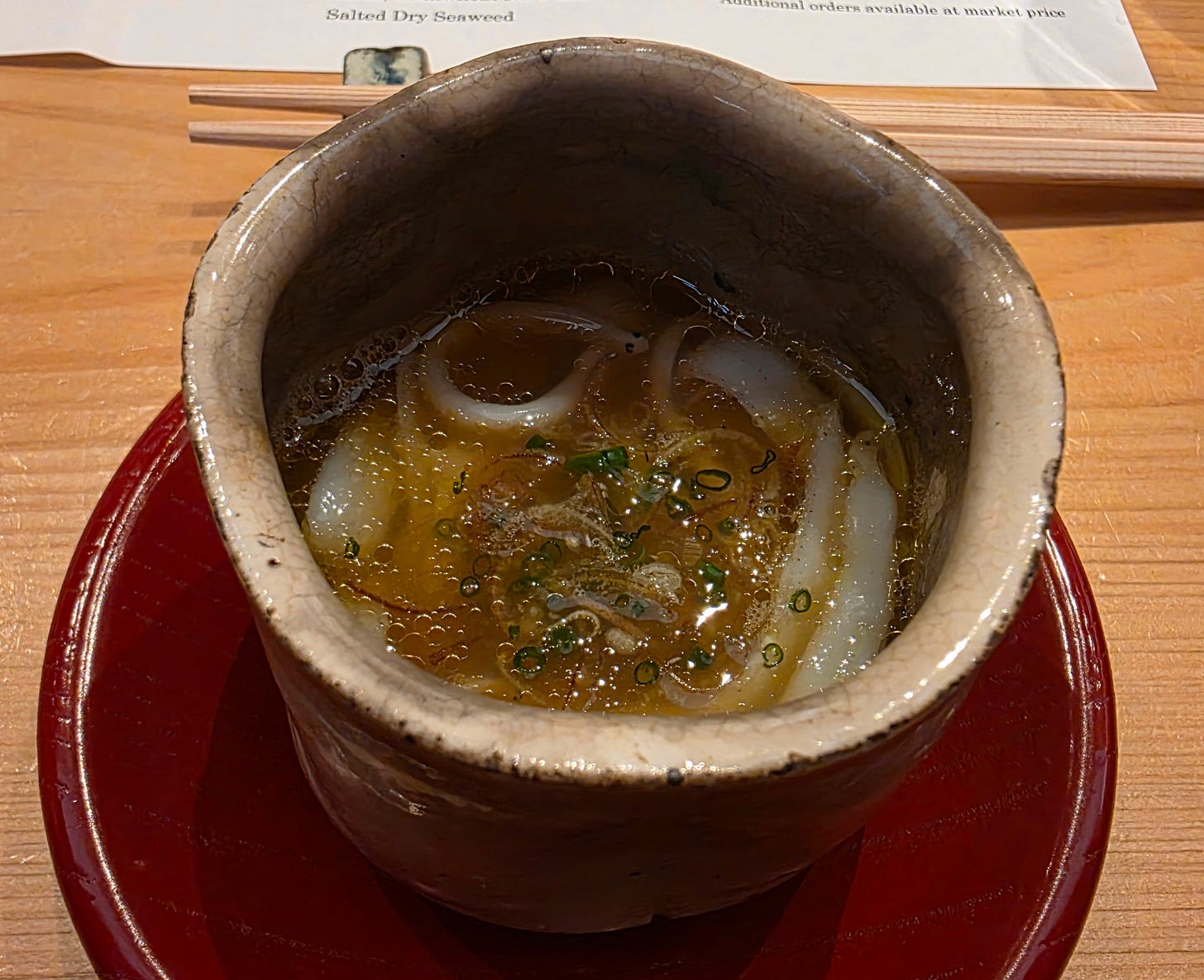

The first dish was a rich, umami bonito broth filled with tiny fillets of baby sea eel. The softness of the flesh made it more likely to be the saltwater conger eel. More subtle and delicate than its bolder freshwater counterpart, the filets were slippery almost slimy, and topped with chopped ginger and scallions to cut through the fishiness.

The next dish was two slices of sea bream, one topped with salted sea cucumber roe and yuzu salt water, and the other with light brushing of soy sauce for contrast. We were encouraged to add a small dab of freshly grated wasabi to add a hit of sinus-clearing pungency.

As we were finishing the sea bream, the master chef got to work preparing the next dish, two pieces of tender octopus tentacle, poached lightly in a soy and mirin mixture, topped with a sprinkle of sea salt and yuzu zest and more of the pungent wasabi. It’s very easy to overcook octopus and get a really tough texture, especially when cooking large tentacles with varying thickness that can cook unevenly. Chef Kaki skillfully managed to keep the octopus incredibly melt in the mouth tender.

Moving quickly into one of the signature dishes at Sushi Shikon, two large pieces of red sake braised monkfish liver, topped with some of the braising liquid. With a rich, high-fat content and custard-like texture, monkfish liver is often considered the foie gras of the sea. The traditional fishing grounds for the monkfish are the freezing cold waters off the northern coasts of Japan, and the liver is a very seasonal dish best enjoyed in the deep of winter, when the monkfish has stored up all the fat in its liver.

Another signature dish at Shikon, a giant steamed abalone served with an abalone liver sauce. Similarly to the octopus, abalone is another dish that is difficult to cook perfectly. It gets very chewy and tough if overcooked, and getting such a large abalone cooked though without overcooking is a testament to Chef Kaki’s skill. The abalone was cut into small slices, and served with a sauce made from its liver, with a bit of sake, soy and mirin to temper the bitterness. This created a thick, umami sauce with hinted of earthiness and bitter that complimented the clean flavour of the abalone. After finishing the slices of abalone, Chef Kaki placed a small ball of sushi rice on to the plate to allow us to mix with the liver sauce and finish every last bit of it.

The final appetizer was a beltfish chargrilled on a skewer over Japanese hardwood charcoal, and topped with a puree of white radish, yellow chives, buckwheat and salty seaweed. The belt fish is a long, ribbon-like fish, with white, flaky flesh. The skin tends to crisp up under heat, so typical preparations would be grilling as Chef Kaki did here, or aburi-style preparations. Personally, I thought the puree was a bit much, and a light sprinkling of salt over the crisp skin would’ve probably been enough.

Moving on to the main event, the apprentice started grating more wasabi in preparation for the sushi courses.

Slowly, deliberately and methodically, the chef and his apprentice started preparing slices of fish for the nigiri, cutting each piece down to exacting dimensions, briefly marinating some pieces, cross-hatching others or making shallow parallel slices to enhance the texture or to allow the flesh to better hold sauces.

As the patrons sitting around the bar patiently waited for the chef to finish the preparation, we all started chatting with the chef about his favourite food around the world, how he thinks about sushi and what other restaurants to try. We didn’t manage to get a favourite out of him, but he did say that the quality of seafood was best in Japan, followed by Hong Kong, then Taiwan, but he wouldn’t recommend going for sushi in Taiwan. When asked for his opinion on “fusion” cuisine, his curt reply was “confusion”, and a laugh. Interestingly, when asked about his favourite comfort foods, he mentioned that young people like drinking at Izakayas, but in his day, meeting a friend was done over soba. In busy metropolitan Tokyo life, two salarymen would meet at a soba restaurants, drink and catch up over appetizers and a few beers, finish off with the soba and head home.

At this point, the alcohol had started kicking in, and many of the patrons had brought their own alcohol. After drinking with the chef, the patrons started offering others pours from their bottles, and I somehow ended up with a glass of Yamazaki 12 year, my sparkling sake, as well as another glass of sake in front of me.

Finally, the preparations were complete, and we were presented with all the slices of fish for the nigiri ready to go. From left to right:

Gizzard Shad, a small oily fish similar in flavour and texture to mackerel. This fish in particular is often used as a benchmark of a chef’s skill, as it requires an meticulous process of washing, salt curing and marinating to avoid its natural fishy flavours. The end result is a balance of sweetness, tangy acidity and rich umami.

Otoro, the fattiest part of a bluefin tuna belly that was expertly cut, revealing the deep fatty marbling, then lightly marinaded to bring out additional umami. The fattiness and mouthfeel of the cut is more similar to a piece of wagyu beef and a complete fat bomb in the mouth.

Chutoro, a slightly less fatty and more meaty piece of the bluefin tuna belly that was also lightly marinaded. A deeper red than the otoro, a less intense fat bomb than the otoro and a much more balanced cut.

Golden Eye Snapper, a seasonal cold water deep-sea fish prized in Japanese cuisine that I haven’t tried before

Cuttlefish, poached lightly and left to age for several days to enhance the natural flavours. When the chef was asked about how he tells another sushi master from a novice, he mentioned the subtle flavours developed by aging cuttlefish, and that while we may think that sushi is purely a function of the freshness of the fish, for him, there is a lot of subtle nuance that can be developed by a brief aging or a light marinade.

First up was the cuttlefish, with a series of shallow parallel cuts to better hold on to the brushed on soy. Otherwise the sauce would slide of the dense, springy flesh of the cuttlefish. I’m normally not a huge fan of cuttlefish as it can be unpleasantly chewy if not prepared well, but there was no hint of that here.

It was at this point that the chef explained that most sushi chefs use rice vinegar for their sushi rice, but he preferred using red vinegar made from sake lees, or the leftover residue from sake brewing. The red vinegar adds a dark reddish-brown colour to the rice, as well adding deep umami flavours with a hint of sweetness.

The Golden Eye Snapper was up next, glistening with a light orange colour. There was almost a crunch in the springiness of the meat and a clean, sweet flavour. One of my favourite of the night.

Getting into fattier and heavier pieces, the Chutoro came next. The marbling of the fatty tuna belly could be clearly seen, as well as the glisten of a light brushing of soy sauce.

The Otoro was a complete fat bomb in the mouth. The hit of pungency from the wasabi helped cut into the intense fattiness of the meat.

The Gizzard Shad was an unexpected highlight. Well balanced, slightly fishy, with a natural oiliness on the tongue. Much more complex than the Otoro and I would’ve liked another one of these.

A pressed Mackerel roll. More Mackerel than rice, and similarly to the Gizzard Shad, oily, fishy, balanced out by a bit of salt and sour from the curing process. Pressed into a perfect cylinder and precisely cut. Well done.

Next was an omakase favourite, two kinds of Hokkaido Uni (sea urchin) on rice. A bright orange Uni from the short-spined sea urchin, the bright orange being developed from a diet rich in carotenoids in its diet of kelp and algae and another paler yellow Uni, usually from a younger purple sea urchin. The Uni was served in a small bowl on top of a small sushi rice ball with a tiny dab of wasabi on top. Rich, decadent and delicious!

Some giant poached Tiger Shrimp were brought out, de-skewered and delicately deveined before being lightly smoked in a contraption the chef brought out. I didn’t end up tasting any smoke, but I’m guessing he wasn’t steaming an already poached shrimp. After a brief rest, the Tiger Shrimp was pressed into the nigiri and presented simply to us. Sweet, meaty and a giant mouthful!

The final piece of nigiri was a Saltwater Eel (Anagi). Leaner and less oily than the Freshwater Eel (Unagi), it’s a bit lighter, more tender and more delicate for an almost fluffy texture. Always a hit and I tend to see this at higher end omakase restaurants, where Unagi is often delivered in bulk, grilled and slathered in a sticky, sweet sauce on top of rice in a bento box.

The final piece, signifying the end n a omakase dinner, the Egg Castella. A dense, moist cake that is deceptively difficult to master and is a showcase of a chef’s ability to control texture, flavour and aroma simultaneously.

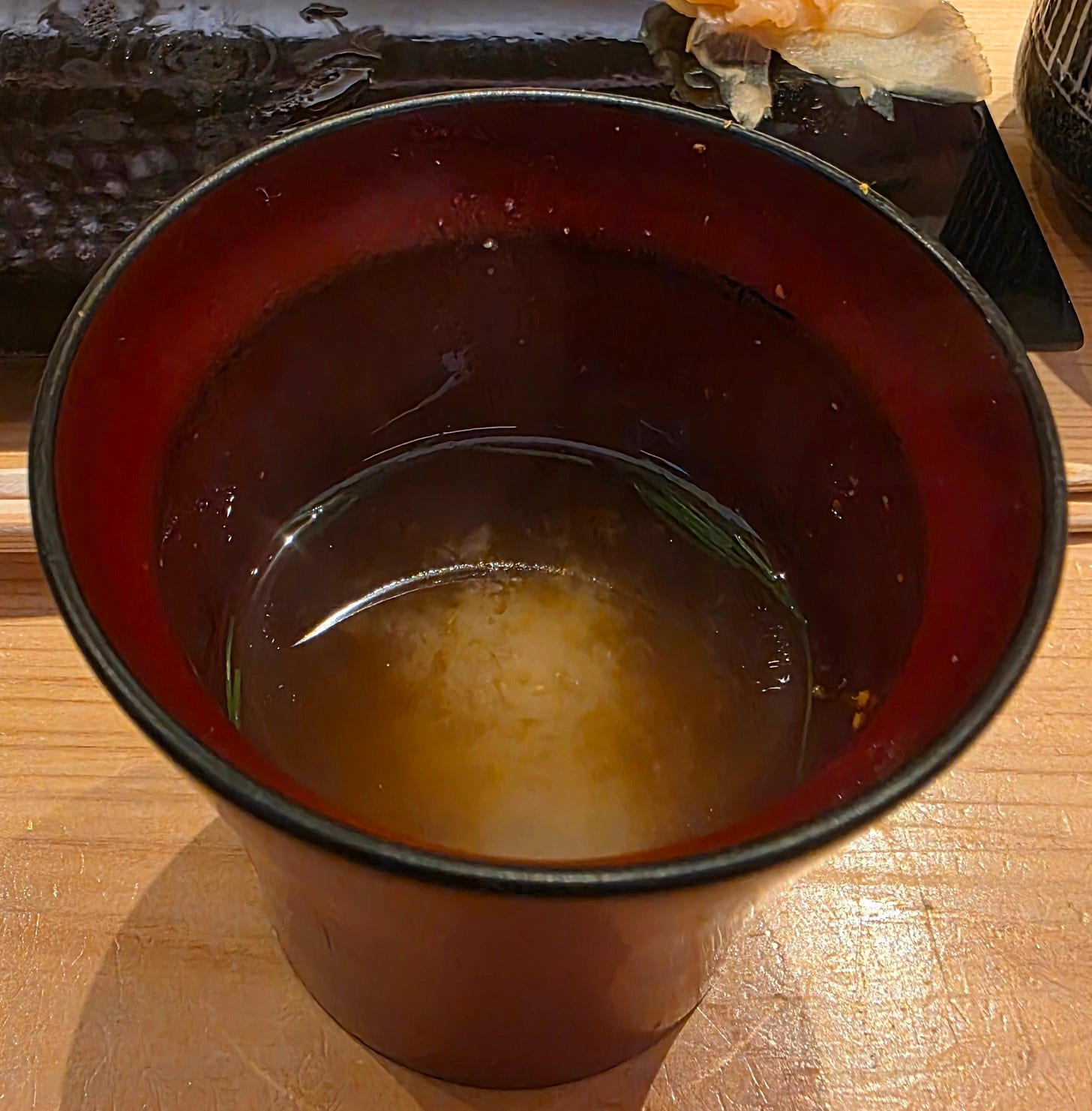

A shot of warm miso soup rounding out the meal and preparing us for dessert. As many of the patrons were avid diners and travellers, a heated discussion arose about the best restaurants in Tokyo. We couldn’t get Chef Kaki to recommend any sushi restaurants outside of his master’s, so we started asking him about other cuisines. He was humbly deferential, but did make a quip that he thought Italian food was better in Tokyo than Italy, a point that a chef friend of mine made recently as well.

Finally, the dessert - slices of Japanese strawberries and mashed azuki bean wrapped in a daifuku mochi wrapping.

Overall, one of the best sushi counters I’ve been to and comparable with the best in Tokyo. Chef Kaki is jovial and friendly and I find that the difference between a good and an amazing experience at a sushi counter is often as much about the interaction with the chef - learning about his craft and his inspiration and us learning some of the subtle nuances about the complex art of sushi. The most memorable sushi counter experiences have been with friendly chefs and patrons where we’re chatting, cracking jokes and drinking together. On both the food and the atmosphere, Sushi Shikon was a absolute hit. Would return!

Total Damage: 4900 HKD/1 person