Dinner by Heston Blumenthal

A Gastronomic trip through British History in London, UK

There’s a history between me and Dinner by Heston. I first visited on June 5th, 2018 and had a miserable time. I remember it vividly - It was one of my first experiences with a Michelin star restaurant, and I had the three course a la carte - the meatfruit, the duck and the tipsy cake. Normally, all three are big hits. I don’t know what it was, perhaps a mismatch of expectations, perhaps I was just in a bad mood. I remember the date and the meal vividly because the next day, through no fault of my own, there was a massive fire at the hotel, shutting down the restaurant for months.

Over time, the restaurant reopened and I’d heard the accolades and positive reviews. Six years later, I decided to give the restaurant another try.

History is what Dinner by Heston Blumenthal is all about, diving into cookbooks from early British history, trying to recreate the theatre of Tudor dining experiences, working with food historians to compress history into a series of dishes that walk us through the history of the British empire. The dishes are often adapted from old English cookbooks and each dish comes with a story explaining its origins and how it was developed.

First opened in 2011, the restaurant immediately earned its first Michelin star in its first year of operation, and earned its second in 2014 which its held ever since. The kitchen was originally run by Ashley Palmer-Watts, who came over from running Heston’s three Michelin star restaurant, The Fat Duck. Adam Tooby-Desmond started at the restaurant in 2017 and took over as its latest head chef in 2023. He was also the chef who brought over and described many of the dishes to us during our experience.

Arriving at the opulent Mandarin Oriental hotel in London, we walked into the grand entrance, up the stairs, and turned to the left to arrive at a counter with an oddly glowing pineapple behind it.

As the hostess explained, pineapples were a symbol of status and wealth in 1700s Britain. They did not grow naturally in the cold British climate and had to be imported from the central American colonies at great expense. A single pineapple could be worth thousands of pounds and would be rented out to be displayed at high society events.

Eventually, farmers developed methods to grow pineapples in British weather, but their tropical temperament required extreme measures to successfully cultivate the fruit - round the clock heated air to replicate the tropical environment, heated soil to prevent frost damage and years of time and attention from seedling to marketable fruit.

In usual fashion, I showed up early, so the hostess seated me at the gold adorned Mandarin Bar and ordered a drink as I waited for my companion. Eventually, and characteristically late, she arrived, and we were walked past two glass wine cellar rooms, past the main restaurant and tucked into the special chef’s table beside the kitchen.

The chef’s table comes with a special tasting menu, and a chamberlain to explain each dish. It’s located right beside the open kitchen, and throughout the night we could watch the kitchen in action, with orders being barked out and a chorus of “yes chef” returning.

An indent in the table was based off a paint palette in an allusion to the meal being a piece of art, but also in practical manner, allowing the chamberlain to efficiently reach every point on the table.

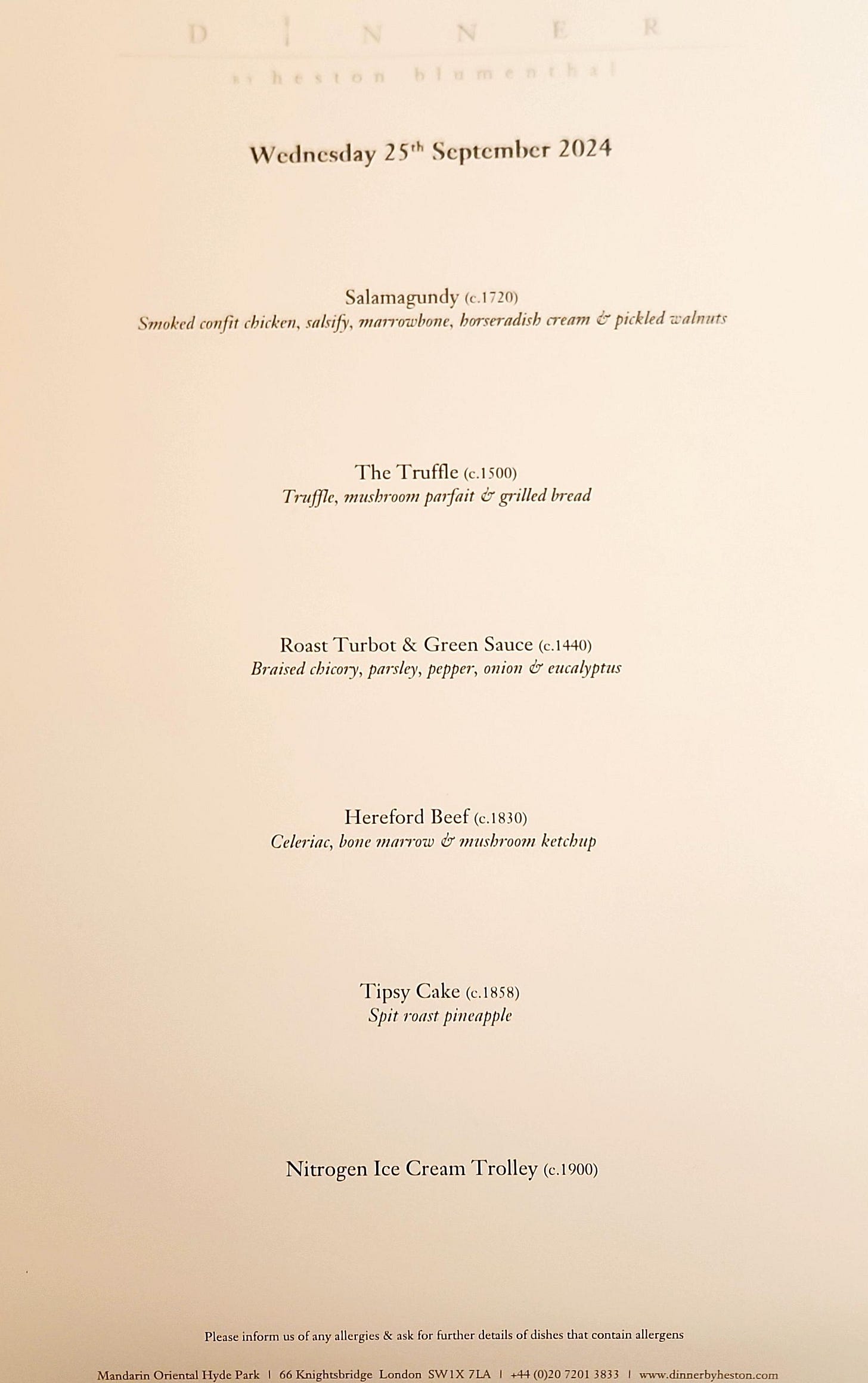

Within a small black box waiting for us at our table was a scroll with our printed menus for the night, customized with all of the adjustments made for our dietary requirements.

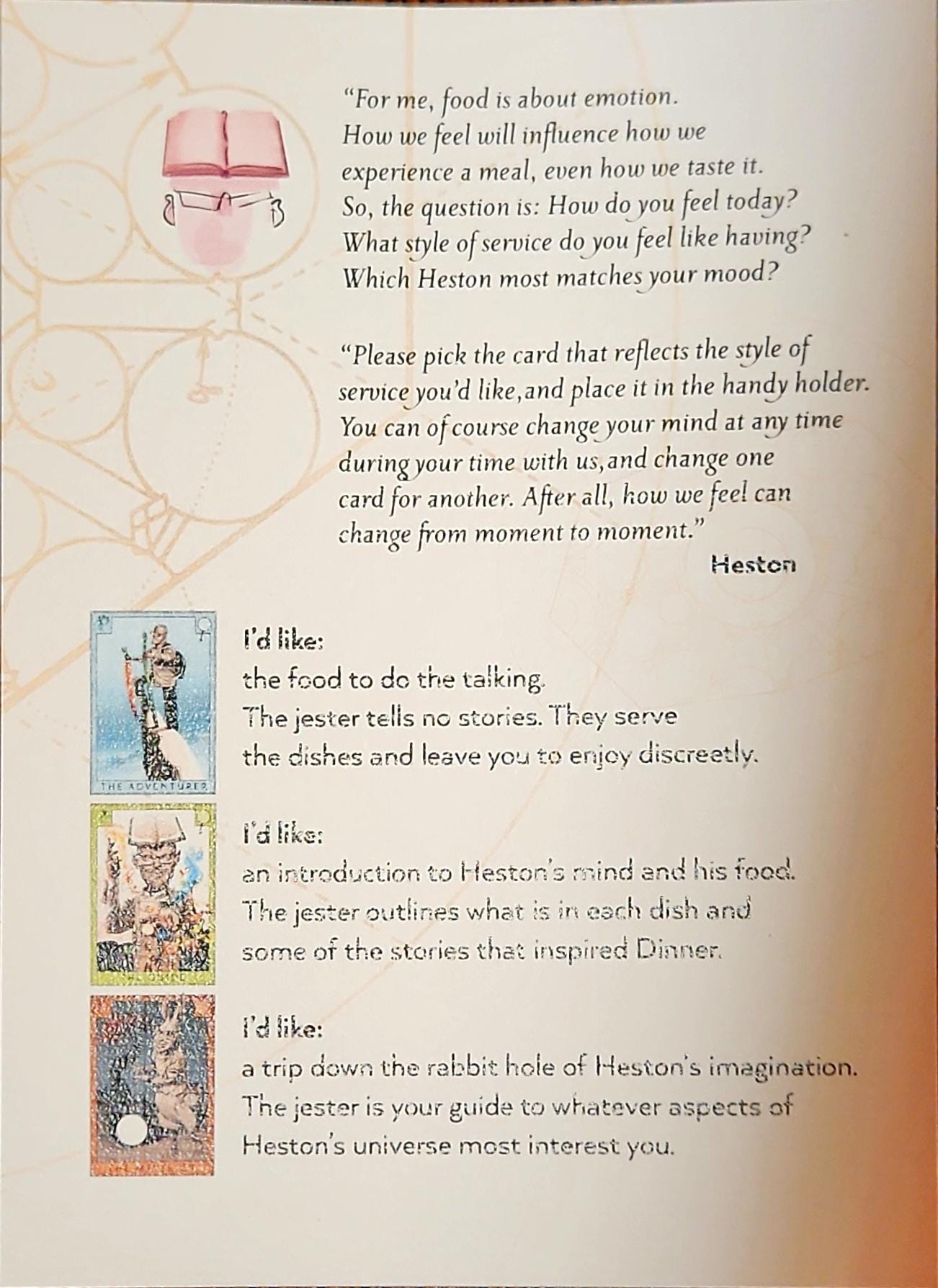

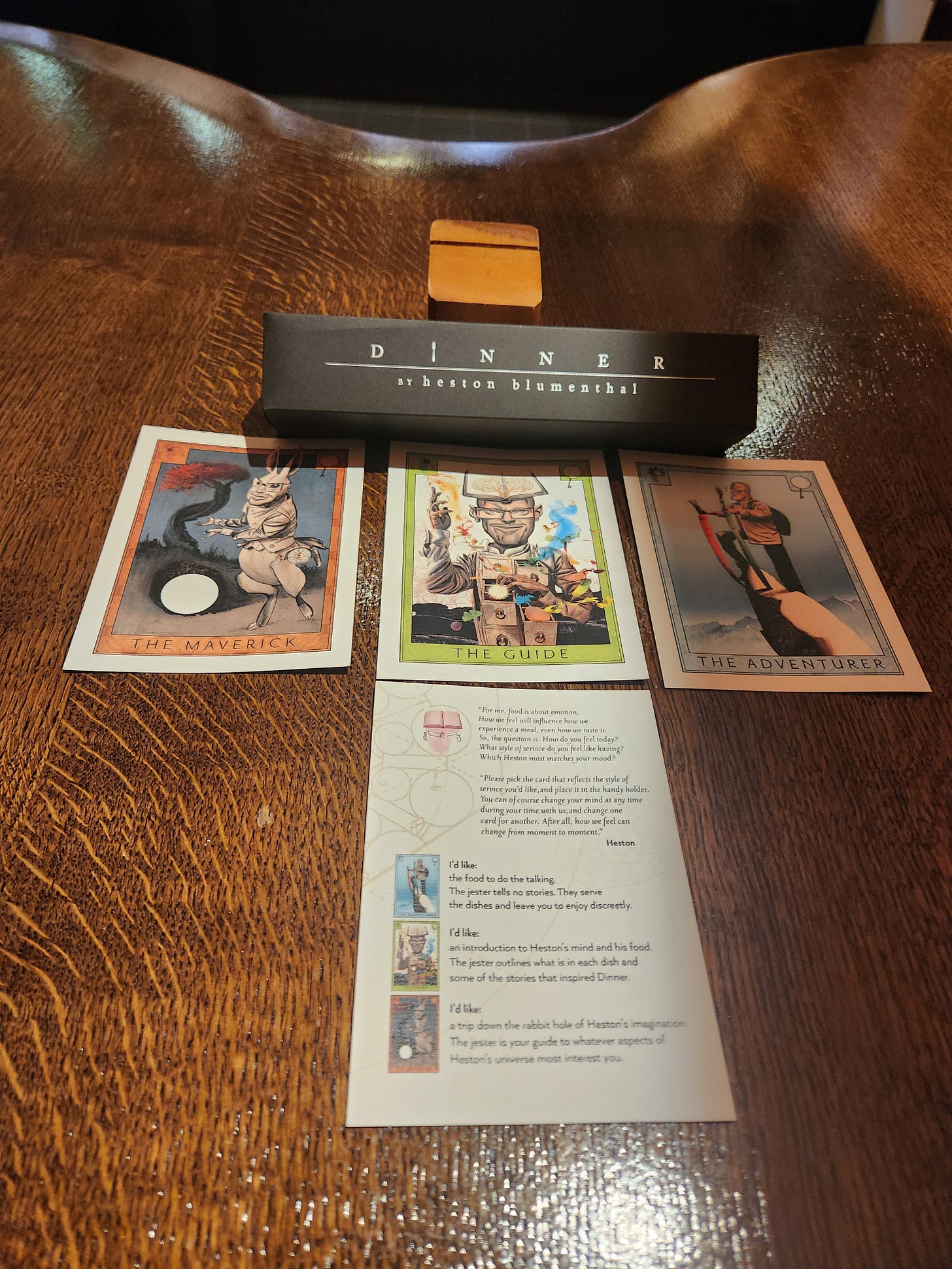

We were given three cards to put on a stand to dictate how much explanation or talking we wanted our chamberlain to do. We wanted to know about the dishes, as well as the history and inspiration, so we put both the guide and the maverick on the stand.

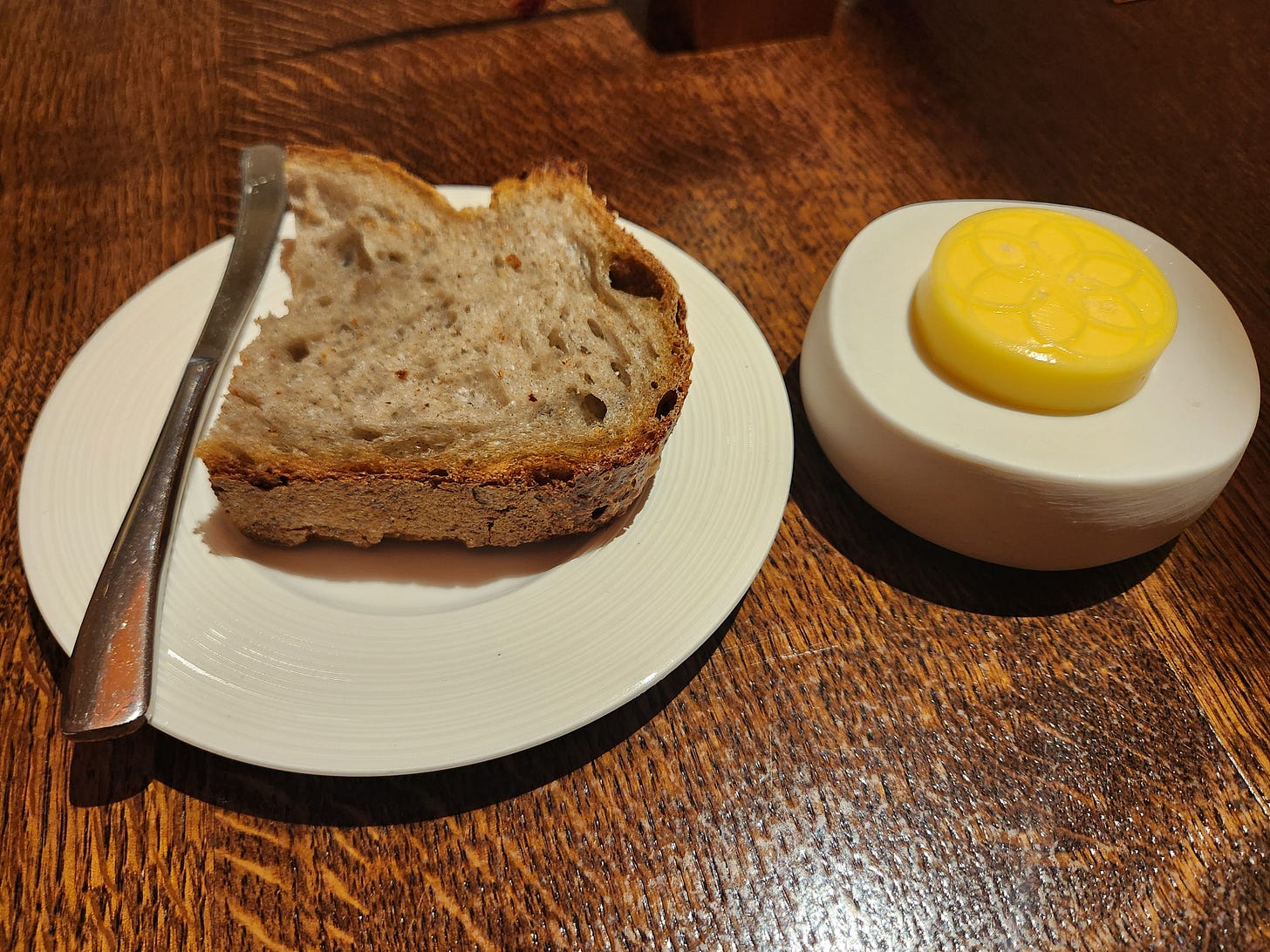

A thick slice of sourdough with some Guernsey butter. The sourdough at Dinner is made with Campaillou flour, a blend of rye and malt. The dough is intentionally over proofed to create a light dough with lots of air pockets before baking.

I ordered the fan cocktail, one of seven cocktails derived from the story of the six blind men and the elephant, containing rum, ginger and mango. My companion ordered the lychee delight, a mix of an nonalcoholic apertif, lychee, raspberry cordial, elderflower, and tonic water. Neither drink was particularly good nor memorable.

A trolley with two siphons and a frosted glass bucket of liquid nitrogen was wheeled over, and one of the chamberlains explained the amuse bouche and started preparing it.

He siphoned an egg white mousse on to a spoon, immersed it in liquid nitrogen until the outside of the mousse set, forming a cold hard shell. There’s a hard crunch, like a cold meringue, but a light, fluffy interior with very faint lime sour flavour. We were told that the original receipt was developed at The Fat Duck, and they could do any cocktail flavour.

The Salamagundy - a bit of crunch from the bitter endive and chicory leaf salad with bamboo shoots, amazingly juicy smoked confit chicken on a rich bone marrow and horseradish cream dressing. Salamagundy is not one recipe, but refers more to the presentation of salad with many different individual ingredients plated in geometric designs or assembled in careful layers. Like its name implies, each of the ingredients was distinct, well flavoured on their own but also worked well when combined together. A very promising start to the meal, and one of the best salads I’ve had in London.

The signature meatfruit, a recipe originally from the 1300s - a foie gras and chicken liver parfait, coated in a tangerine jelly made to look like a mandarin orange. The chef estimated that it was only 30% butter, but I would’ve guessed much closer to 50%. Rich, whipped to the point of fluffiness, and spread on a piece of grilled sourdough, brushed with rosemary thyme garlic oil. Delightful, and it’s obvious why it’s one of the signature dishes at Dinner.

The vegetarian option is a mushroom parfait, made to look like a truffle. Similarly to the meatfruit, about 30% butter, but with deep umami mushroom flavours instead of chicken liver. Again, deeply rich, light, and luxurious, spread on a perfectly toasted slice of herbed sourdough. Apparently, the reason they chose mushroom for the vegetarian option is because they went through a vintage cookbook of a hundred mushroom recipes by Kate Sargeant and in it, it said that the most meat-like vegetables were mushrooms.

The first main course, a piece of turbot with a historic “green sauce” topped with kale and pearl onions with some braised chicory. The pickled pearl onion added a bit of sour, while the green sauce tasted of parsley, garlic and butter, with some infused eucalyptus. Surprisingly, the chicory was quite sweet, with some of the expected bitter aftertaste. The turbot was lightly roasted and one side seared to get a crisp crust.

We were told that the green sauce was stolen from French cuisine after a lot of cross pollination between French and British cuisine during the 100 year war.

The second main course, a perfectly medium-rare piece of Hereford beef served with Hen of the Wood mushrooms, and a buttery celeriac puree, topped with a rich bone marrow and tarragon jus. Absolutely amazing - the steak was seared and left to slow roast slowly above the custom built Josper charcoal oven, so tender it basically melted before the knife.

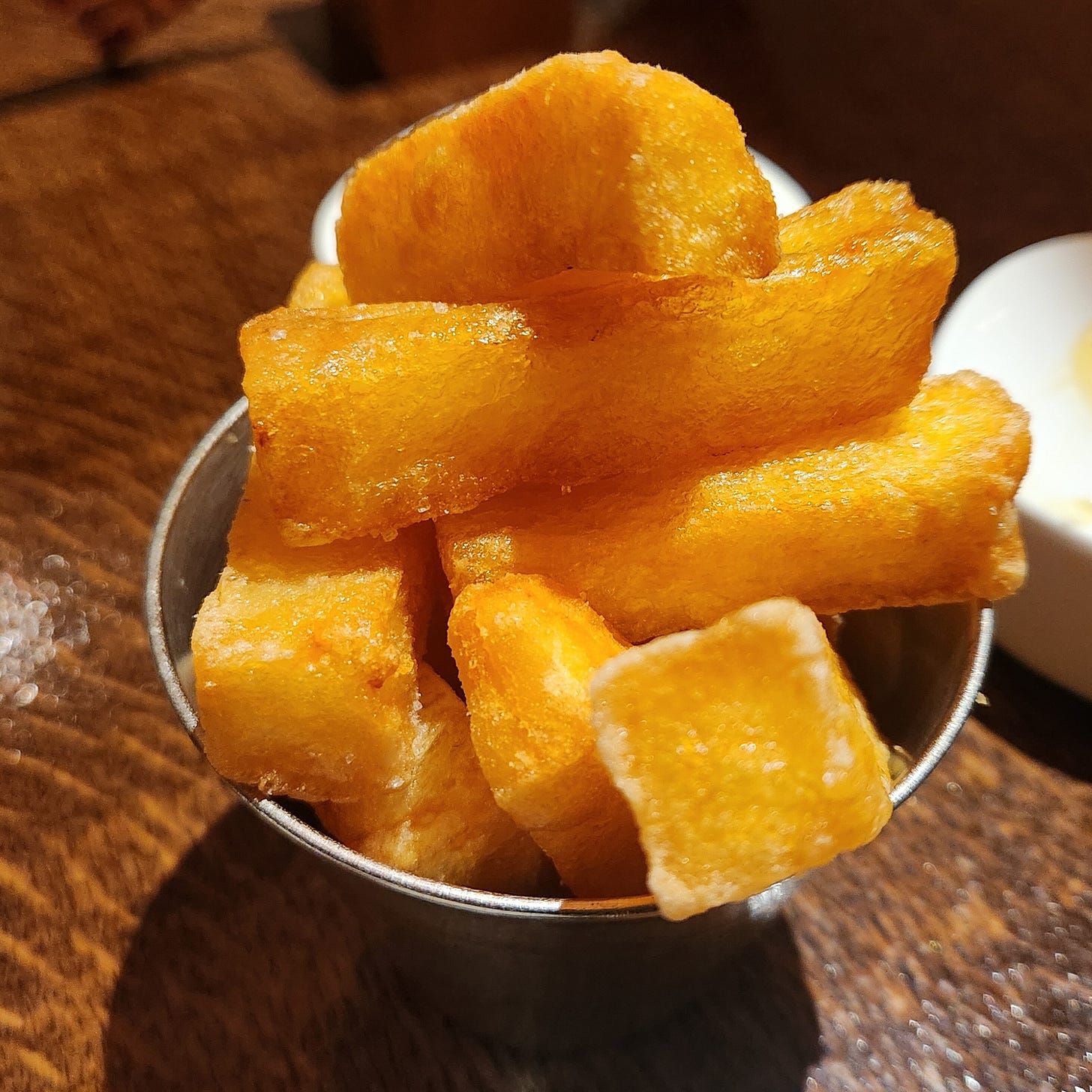

Alongside the steak came some of Heston’s famous perfectly imperfect triple cooked chips. Thick cut, and insanely crispy along the edges, while moist and mealy inside. Among the best chips I’ve ever had in London, rivaling even Hawksmoor’s legendary triple cooked chips.

The first dessert, another signature dish at Dinner, the tipsy cake, a sugar-crusted sweet brioche, slathered with a vanilla custard creme. Reminded me a bit of a Hong Kong pineapple bun, and a slice of pineapple, slow roasted for 4-5 hours and glazed with an apple caramel every 30 minutes and fork tender. Both the pineapple and tipsy cake were incredibly sweet, but after the intense sugar hit of the tipsy cake, the pineapple was sour in comparison. Both the tipsy cake and pineapple were rich and filling and we were only able to finish about 2 slices of the tipsy cake before we were stuffed.

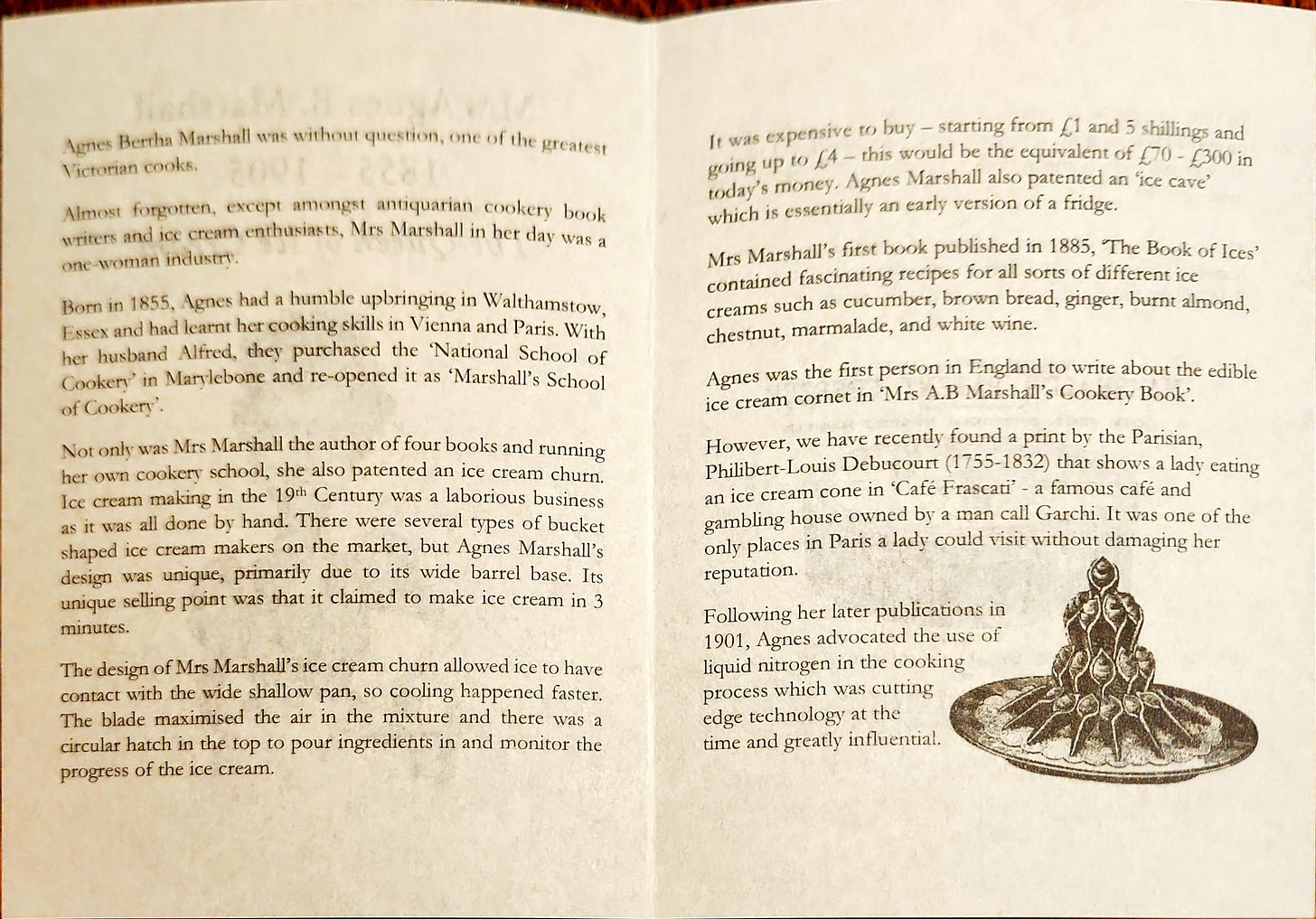

In a prelude to the second dessert, we were handed a booklet, explaining the life and accomplishments of Agnes Marshall, the Queen of Ice Cream.

Our chamberlain wheeled out a trolley and started the show, pouring a large amount of liquid nitrogen into a mixing bowl, followed by a vanilla egg custard. Turning the hand crank for about 90 seconds allowed the egg custard mix and incorporate air bubbles as it froze into tiny ice crystals, forming the ice cream. The ice cream was scooped into a delicately thin sugar coated cone, and topped which our choice of toppings.

I chose dehydrated marshmallow and raspberries, which reminded me a bit of the marshmallows in lucky charms cereal, while my companion chose chocolate and sea salt. In contrast to the intense sugar high of the tipsy cake, the ice cream was not particular sweet, and it was the toppings and the cone that added the sweetness. The ice crema formed an almost neutral vanilla base for the toppings to shine. Amazing.

Finally, the petits fours, crispy tart shells with chocolate ganache droplets airbrushed gold. By this time, we were completely full, and didn’t manage to eat them.

In comparison to my first visit to Dinner by Heston, this was a much better experience. In fact, this was one of the best dinner experiences I had this entire London trip! Best of all, no fire afterwards.

Total damage: 530 GBP/2 people